The Environmental Protection Agency has had a busy month when it comes to PFAS regulation (aka per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances). In the course of a few short weeks in April, EPA finalized new drinking water standards under the Safe Drinking Water Act, finalized the listing of PFOA and PFOS [1] as hazardous substances under CERCLA, and released a major update to guidance on destruction and disposal of PFAS.

New Federal Drinking Water Standards for PFAS

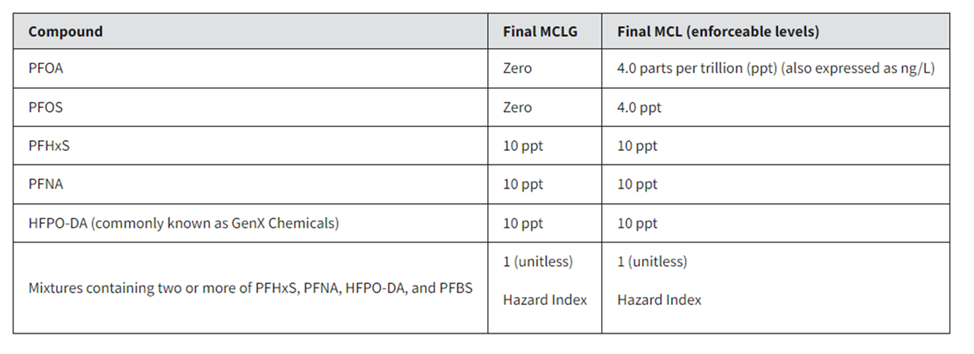

EPA finalized the first federal drinking water standards for PFAS under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) on April 10. The standards establish maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for six PFAS compounds:

Chart source: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

EPA also established a MCL goal (MCLG) of “zero” for PFOA and PFOS, based on the agency’s position that there is no safe level of exposure to these compounds. Public water systems [2] will have three years to complete initial monitoring (by 2027) and five years to reduce the applicable contaminant levels (by 2029). Numerous states have already established standards for PFAS in drinking water, but in light of EPA’s new regulations, all states will be required to ensure their PFAS limits are at least as stringent as the new federal limits.

Billions of dollars of federal funding have been pledged to address PFAS in drinking water. $9 billion has been allocated under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to address emerging contaminants (including PFAS), including $1 billion in additional funding through EPA’s Emerging Contaminants in Small or Disadvantaged Communities Grant Program.

$12 billion is available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to assist with general drinking water improvements, including improvements addressing emerging contaminants and PFAS.

While billions in federal funding may be available, public water systems required to comply with the new standards potentially face significant unknown costs associated with meeting the limits. Many public water systems have already filed lawsuits against suspected sources of PFAS contamination, and the new limits are likely to cause more water suppliers to seek cost recovery through litigation. In addition, EPA’s decision to set the MCLGs for PFOA and PFOS at zero based on health risks is an indication that more regulatory action and more litigation are imminent.

PFOS and PFOA Listed as Hazardous Substances Under CERCLA

On April 19, EPA released the pre-publication version of the final rule to designate PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). The rule will become final 60 days after it is published in the Federal Register.

Designation under CERCLA means that releases of PFOA and PFOS will be subject to CERCLA’s strict liability cost-recovery cleanup scheme. This will undoubtedly lead to more sites qualifying for the National Priorities List and potentially sparking the reopening of some previously closed sites. Practically speaking, the new designations will likely lead to a flurry of new CERCLA litigation over cleanup and cost recovery.

In recognition of the impending wave of new sites and new litigation, EPA concurrently published guidance on PFAS enforcement discretion intend to pursue. Specifically: does notunder CERCLA. In a signal of the scope of the new hazardous substance designations, the guidance does not focus on the targets of new EPA enforcement; rather, the guidance indicates those entities that EPA

- Community water systems and publicly owned treatment works,

- Municipal separate storm water systems,

- Publicly owned or operated municipal solid waste landfills,

- Publicly owned airports and local fire departments, and

- Farms where biosolids are applied to land.

After the initial version of the rule was proposed, industry and public entities worked to persuade EPA to include protections for these “passive receivers” of PFAS contamination. Whether the enforcement guidance effectively provides that protection remains to be seen.

Updated EPA Guidance on Destruction and Disposal of PFAS

On April 9, EPA announced an update to its 2020 interim guidance on the destruction and disposal (D&D) of PFAS. The purpose of the D&D guidance is to provide a tool to those managing PFAS and PFAS-containing materials by recommending D&D technologies that have “lower potential for environmental release.”

Based on this criteria (and the state of the technology), the updated guidance recommends the following D&D technologies:

- Interim storage with controls;

- Permitted Class I non-hazardous industrial or hazardous waste underground injection wells;

- Permitted hazardous waste landfills; and

- Permitted hazardous waste combustors operating under certain conditions.

The list is consistent with the 2020 guidance and reflects EPA’s current assessment of D&D technology. Although EPA states the list is in “no particular order,” it is notable that the first option listed equates to a “wait and see” approach to PFAS-containing waste. This indicates that—at least in EPA’s current view—D&D technology still needs significant development and improvement. The updated interim guidance also discusses the safety and efficacy of emerging D&D technologies, including mechanochemical degradation, electrochemical oxidation, gasification and pyrolysis, and supercritical oxidation.

Considering EPA’s significant action to regulate PFAS under the SDWA and CERCLA, these new D&D technologies can’t get here soon enough.

The comment period for the interim guidance is open until October 15, 2024 (Regulations.gov, Docket ID EPA-HQ-OLEM-2020-0527).

For more information on these or other PFAS developments, contact Ryan R. Kemper or Suzanne Hart.

Thompson Coburn’s environmental practice group assists clients in all aspects of PFAS regulation and litigation, including class action defense, cost recovery actions, regulatory compliance, and transactional issues.

[1] PFOA is the commonly used acronym for perfluorooctanoic acid; likewise, PFOS is short for perfluorooctane sulfonic acid.

[2] The SDWA applies to “public water systems,” defined as “a system for the provision to the public of water for human consumption through pipes or other constructed conveyances, if such system has at least fifteen service connections or regularly serves at least twenty-five individuals.” 42 U.S.C. § 300f(4)(A).